At the beginning of Hamnet, an opening graphic informs us that the names Hamnet and Hamlet were considered identical during the era of playwright William Shakespeare. In the graceful, empathetic, and compassionate hands of director Chloé Zhao, such a melding is not just a quirk of Old English vernacular. It’s also the otherworldly connection, borne of great tragedy, between Shakespeare’s only son and the timeless play that the young boy’s death inspired.

It’s irrelevant whether or not scholars agree that a direct line can be drawn between the two, because Zhao’s transcendent drama is only marginally about Shakespeare the historical figure (in fact, only once is the character referred to in dialogue as “William Shakespeare”). Zhao’s film, an adaptation of Maggie O’Farrell’s 2020 novel, is ultimately about overcoming grief, and how a couple torn apart by their differing grief mechanisms can come together in understanding and catharsis.

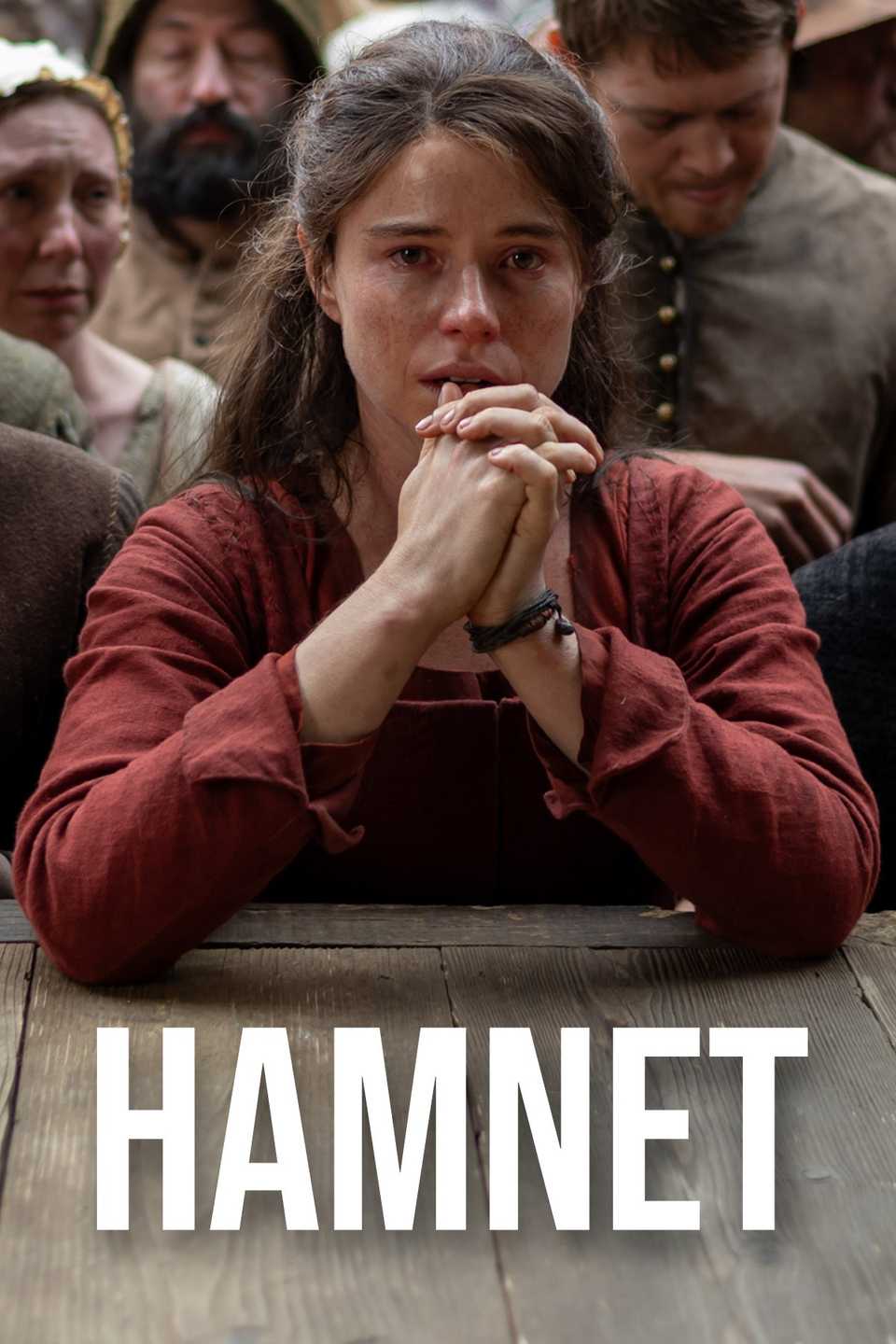

Dipping into her well-established visual playbook to great effect, Zhao (The Rider, Eternals), in only her fifth film as director, turns a husband and wife’s respective trauma responses into near-poetry that blends the internal with the eternal. It helps that the two vessels through which Zhao conveys her message of healing are so intimately attuned to her goals, ones that could have read as too arthouse ephemeral in lesser hands. Paul Mescal (Aftersun, Gladiator II), despite his Oscar-nominated success, has never found a role that so perfectly suits his unique combination of soft masculinity and sad-eyed melancholy…until now. At turns, his Shakespeare is fiery, frustrated, and wounded. As the film, co-edited with emotional delicacy by Zhao and Affonso Gonçalves, progresses, Shakespeare becomes physically estranged from his family as he pursues his writing career, then spiritually estranged from them after the death of Hamnet. Shakespeare’s silent, buried trauma runs against the bottomless pain expressed by his wife, Agnes, played with fearless intensity by Jessie Buckley. Here, Agnes is conceived as an earthy spirit whose connection to the trees and the soil of her beloved Stratford, England don’t protect her from — in fact, they foretell — her future agony. Her performance is so deeply raw that the film, which is essentially about Agnes, not William, occasionally reaches something transcendent, especially during its grab-your-hankie, final moments.

Zhao’s film is both deft in touch and heavy in emotion, yet little thought is given to labeling her work melodramatic, although one may consider it when a grief-stricken William recites the opening of Hamlet’s “to be or not to be” soliloquy or when Max Richter’s mournful “On the Nature of Daylight” is deployed (for the umpteenth time in a film or TV series) during a key moment. Otherwise, as in her Oscar-winning work in Nomadland, Zhao connects our shared humanity to the natural world. Agnes is introduced to us as she lies in a fetal position at the base of a large, thick-rooted tree. With her passion for falconry and herbal remedies, she is branded a “child of a forest witch” by disapproving townsfolk. But she’s nevertheless the object of William’s desire. Unlike the free-spirited Agnes, William is a “pasty-faced scholar” who spends his days indoors working as a Latin tutor and toiling away on his plays. Their courtship and marriage are dispatched quickly, although Zhao (who wrote the film adaptation with O’Farrell) incorporates enough visual portents, like the giant hole in the earth that will soon come to great meaning, to ensure that we never shake our sense that the family is destined for dark times.

Indeed, Hamnet doesn’t lack for visual or aural harbingers, as when Agnes, who has already given birth to Susanna (Bodhi Rae Breathnach), predicts that she will be surrounded by two children on her deathbed. So the arrival of twins Hamnet and Judith (Olivia Lynes) suggests that her communion with the veil of nature does not mean that nature is attentive to her needs. And Zhao, working with Director of Photography Łukasz Żal, often places the camera at a slightly elevated distance, as if a ghost is watching Agnes and her family. The film’s central tragedy unfolds in a riveting sequence where Judith lies near death from pestilence, and 11-year-old Hamnet performs a mystical act of transference by dying in her place. Zhao’s ability to get actors onto her wavelength reaches new heights with the pre-teen Jacobi Jupe, who is so deeply effective as Hamnet that his death, and the way she portrays it, justifies all that comes after it. Equally good is Mescal, whose reaction to seeing the covered shroud of his deceased son is absolutely devastating.

Despite Hamnet’s death — or, as we’ll soon learn, because of it — William spends more and more time in London to tend to his nascent career as a playwright. Back in Stratford, Agnes suffers the dual agonies of her son’s death and her husband’s absence when it happened. As William distances himself from Agnes both physically and emotionally, Zhao refuses to pass judgment on his actions. She’s too much the humanist for that. And while it’s true that both characters are defined by their reaction to their shared trauma more than their personalities, it’s what’s underneath the surface — growing, roiling, and needing release — that’s more important. It defines Zhao’s intentions, and it leads to the film’s heart-stopping final stretch. It takes place during the opening of Shakespeare’s Hamlet, which attracts a healthy crowd to the Globe Theater, including Agnes. In watching the melancholy Dane (energetically played by Jacobi Jupe’s older brother, Noah) soliloquize about the thousand natural shocks that flesh is heir to, Agnes reconnects with William by realizing that grief is a monster that can be tamed in more than one way and, for William, that way is his art. It’s a notion that comes off as neither facile nor self-congratulatory from an artist who obviously feels very deeply and who can convey that depth of feeling to the audience. By the end, we recall young Hamnet’s dream of someday working with his father in the theater. In a way, if not the way anyone would wish for, his dream actually came true.

Hamnet opens in theaters on November 26 from Focus Features.

- Release Date

-

November 27, 2025

- Director

-

Chloé Zhao