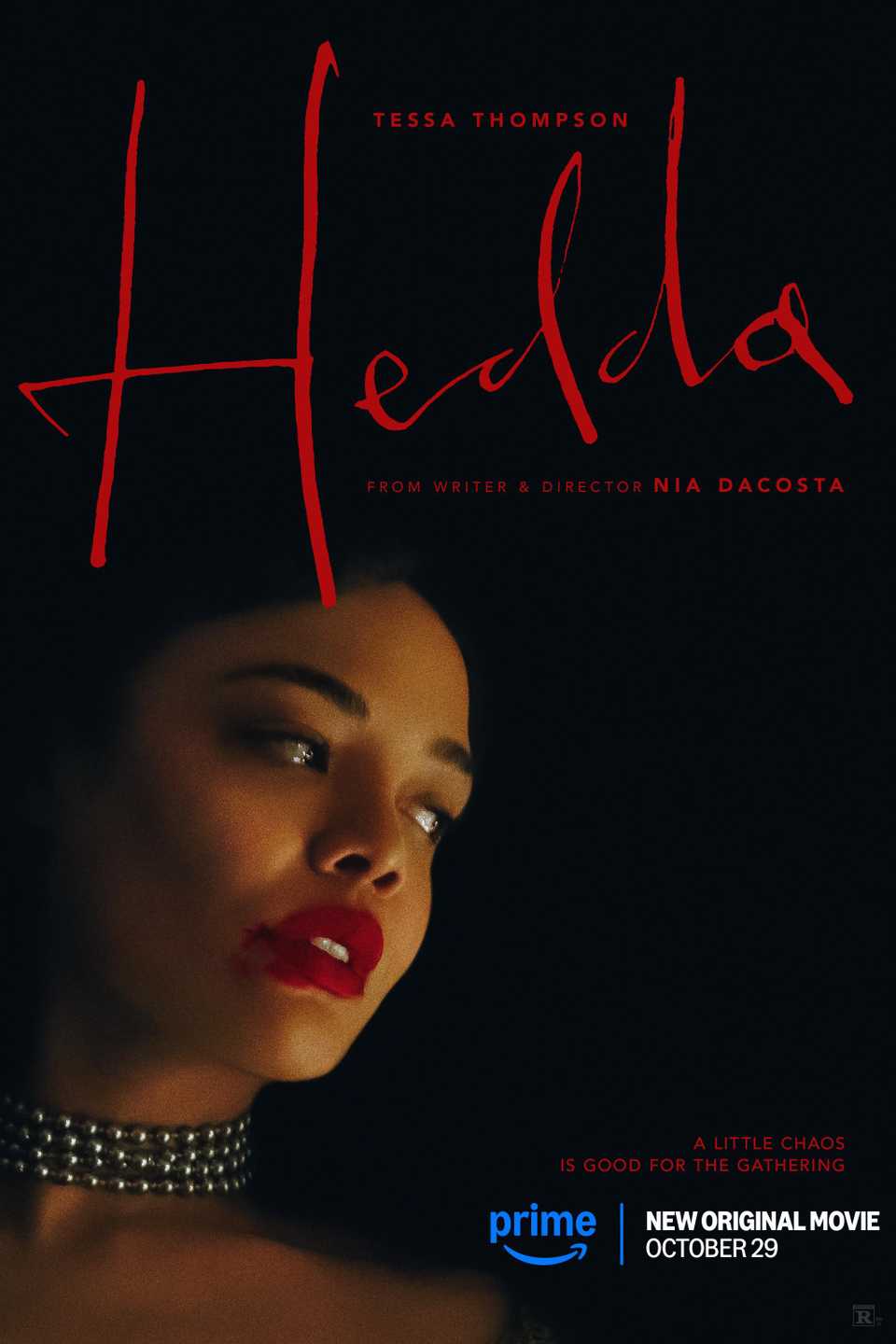

Nia DaCosta’s adaptation of Henrik Ibsen’s classic play “Hedda Gabler” is a deliciously twisted reimagining of the familiar story. DaCosta reunites with her Little Woods star Tessa Thompson to delve into the dark psyche of one of theater’s most unconventional villains, a manipulative woman who hurts just about everyone who crosses her path as she betrays their trust. Updating a number of details, DaCosta finds new ground to explore through the characters, creating an adaptation that feels less like a restaging and more like a monster born anew.

After a brief scene of Hedda (Thompson) being questioned by police, DaCosta’s Hedda restarts at the beginning of the day as the denizens of a large English countryside estate are preparing for a lavish party. The hosts, a spirited Hedda and her new husband George Tesman (Tom Bateman), are spending beyond their means to impress friends, colleagues and George’s potential employer, Prof. Greenwood (Finbar Lynch). Hedda is hiding her own secrets, including a dalliance with Judge Roland (Nicholas Pinnock), but acting every bit the part of a gregarious host. However, when a former flame, Eileen Lövborg (Nina Hoss) and her new partner Thea (Imogen Poots) arrive, Hedda’s chaotic nature sows seeds of mistrust and heartbreak between lovers and competitors alike.

- Release Date

-

October 22, 2025

- Runtime

-

107 minutes

- Director

-

Nia DaCosta

- Writers

-

Nia DaCosta, Henrik Ibsen

- Producers

-

Dede Gardner, Jeremy Kleiner, Tessa Thompson, Gabrielle Nadig

DaCosta’s Hedda looks opulent in an almost sinister way from the start. Giving the film rich, velvety tones, DaCosta and cinematographer Sean Bobbitt bring out the gold and red undertones of each scene, drinking in the conflict like a dark red wine. There’s almost a sepia quality to the movie, giving it a saturated look that feels like an homage to the bygone Jazz Age and wild Gatsby-style parties seen in silent movies. But the image is so crisp, and the camera movement so smooth — especially during an impressive dolly shot when Hedda and Eileen first lay eyes on each other — between Hedda’s wild emotional swings that it feels deceptively calm as Hedda whips up her own storms.

DaCosta brings in a treasure trove of artisans to create Hedda’s world. Production designer Cara Brower and set decorator Stella Fox look like they spared no expense filling the many halls and rooms of the mansion with showy antiques and party favors, including a gorgeous Art Deco chandelier that comes crashing down as the events of the evening start going off the rails. Although there are not many costume changes — the story unfolds over the course of one night — costume designer Lindsay Pugh creates a number of eye-catching designs that tell just as much about the characters as their actions. These include a red dress for Hedda that looks like the one worn at the end of Powell and Pressburger’s 1947 classic Black Narcissus (which, incidentally, shows up in that film to signal madness), and Eileen’s corseted dress, which covers her breasts with a sheer material that, when wet, affects men’s behavior. Oscar-winning composer Hildur Guðnadóttir stitches in both jazz music and breathy discordant sounds that echo the characters’ desperate struggle for control.

Hedda would not be nearly as enjoyable without Thompson’s masterful performance. With a wry smile and gleaming eyes, Thompson’s Hedda behaves like a cat playing with her catch before swallowing it whole. Her appetite is insatiable, as one party guest jokes, and once she’s disrupted one part of the party, she makes her way to a new corner to start more trouble. In a satin dress and beautiful jewelry, Hedda stalks the party like a lioness; she gives the impression that her king George is the one in control, but she’s the first to pounce at the sight of weakness, casually insulting people and wrecking havoc between them. Only Eileen seems to have the ability to match her, but with a seamless heel turn, Hedda shows an abominable side of herself as she attempts to unseat Eileen’s candidacy against her husband’s bid for an academic post. Hoss’ Eileen arrives as an unflappable foil to Hedda’s insincere congeniality. But when Hedda breaks her down, it is piece by piece, and Hoss is as impressive on the way down as when she arrives on screen.

Changing Lövborg’s character from a male former lover to a female one produces a new theme: women fighting for their way to the top of their social and professional ladders. Throughout Hedda’s many interactions, the audience gets a sense of how the character has conformed to certain norms to “fit in,” like marrying well and spending way beyond their means to give the illusion the young couple have made it. But in more than a few scenes, DaCosta shows George forcibly grabbing Hedda by the arm, jealously leading her away from Eileen. His attempt to physically control his wife shows off his own insecurities in the face of other guest’s comments about Hedda’s sexual past. And, however outwardly successful, Hedda still contends with racism: a party guest even comments negatively on her skin color. Hedda will get her revenge on the woman in due time, but it adds a more sympathetic side to the complicated character by suggesting what she’s had to endure to survive in these majority white spaces.

Lövborg, on the other hand, refuses to compromise. She’s an unapologetic lesbian, almost taunting men about how they do not appeal to her. She’s very ambitious, pursuing academics despite the politics and misogyny in the field. These leave her vulnerable in other ways, like a sense of insecurity and a drinking habit that are not immediately part of the strong, independent persona she’s cultivated. She tells Hedda she’s disappointed in her life’s choices: “When will you understand that anything you need in life, you must build for yourself?,” she asks. While there are many reasons why Hedda retaliates the way she does against Eileen, jealousy of her freedom is almost certainly near the top of that list. Then there’s the nervous Thea, who finds herself stuck between a vindictive woman and the flawed woman she loves. She is almost too unprepared for the cruelties of both arenas. Hedda’s sharp tongue takes frequent aim at her, and although she eventually learns to defend herself against the barbs, it costs her a sense of innocence and naiveté — a luxury few independent women can afford.

“My whimsicality has its consequences,” jokes Hedda, foreshadowing early on in the movie that she knows what she’s capable of, but shrugs off any guilt. She feasts on glamour and misbehavior, on sexual tension between both genders and the chance for further social climbing. The only person Hedda is really supporting, both in DaCosta’s vision and in Ibsen’s, is herself. She embodies a kind of cruelty that no one should aspire to, but that’s fascinating to watch.

From Amazon MGM Studios, Hedda is playing in select theaters now, and premieres on Amazon Prime on October 29.